A Walking Tour

Thailand’s temples are usually encircled by a wall. Within you’ll find open grounds with gardens and walkways between the buildings. Some wats may even include food vendors and parking areas. The main structures are easy to spot, even from a distance, with their distinctive, multi-layered rooftops in green and orange tiles. While the simplest wats may only have two or three buildings, more elaborate compounds can house ten or more.

Once you enter the complex grounds, the first thing your likely to notice are the buildings’ facade walls. From festooned relief sculpture, and colorful appliquéd mirror, or ceramic tile fragments, to wildly complex pediments (gable boards above entryways) or friezes and murals depicting Hindu gods, heroes, epic battles and the Buddha’s lives, a wat is alive with imagery.

Strange, mythic beasts, giant monster-like guardians, Chinese lions, enormous snakes and other creatures are usually scattered throughout the compound or used as architectural accents, further adding to the seeming clutter of these holy places. But once you are aware of the stories behind all this detail, you can begin to find a semblance of logic within the apparent chaos.

What’s Wat?

The principle and most sacred structure at a wat is the bot, also known as an ubosot or ubosatha. This is the monks’ ordination hall and is set on consecrated ground. You can recognize a bot because it is encircled by water or demarcated by eight sima or carved boundary stones, located at the four cardinal points and four corners. In many wats, the bot remains closed except during religious functions, while in others, this is the primary location for the laity to go in order to make merit (improve their good credit toward future lives) in the form of candles, flowers, incense or coins offered to a Buddha image.

The viharn or vihara is often the largest structure of a wat. Either rectangular or cruciform in shape, this is the assembly hall, where the laity can listen to monks reciting Buddhist scripture, make merit, or check their fortune by shaking a container of sticks until one falls out.

Historically, the viharn was the place of learning for the laity, so it is not uncommon to find mural paintings of the Buddha’s lives and teachings covering interior walls (although interior walls of any structure may include murals). Buddhists say that Prince Siddartha lived 547 lives prior to his enlightenment. His final ten lives tend to be the most popular, but not the only mural themes. Hindu epics, particularly the Ramayana (known in Thailand as the Ramakien) is another popular subject, with the most famous example to be found along the gallery walls of Wat Prah Keaw at Bangkok’s Grand Palace.

Small village temples throughout the country often boast murals featuring local folk heroes with distinctive local style. Nan Province, for example, is famed for its 18th century renderings that depict more commoners going about their daily lives (including women smoking) than royalty; and more folk hero adventures than Buddhist tales.

Chedi is the Thai word for stupa. These domed structures are used as monuments to house a Buddhist relic or the ashes of a monk or important person. Most large chedis sit atop a building that contains Buddha images, and may also include interior murals. A typical, Thai chedi, whose stylistic roots stretch back to Sri Lanka via the first Thai kingdom of Sukhothai, is shaped like a bell topped by a spire, and often sits upon a redented base (a series of recessed, rising levels).

A prang is another style of chedi that stems originally from the Khmer empire but had a renaissance of sorts during Thailand’s Ayutthaya period. A prang is very distinct and looks like an ear of corn with many carved niches along its tall, slim exterior. Excellent examples of both chedi and prang can be seen at Wat Prah Keaw. Wat Arun, across the river, is famed for its ceramic-covered prangs, while Wat Mahathat in the southern city of Nakhon Si Thammarat is the place to go to find the kingdom’s most massive chedi, weighing in at more than 200 kg and sporting a spire made of solid gold.

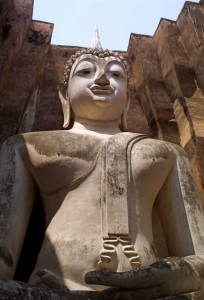

A mondop is a square-shaped, open-sided building used to shelter Buddha images or religious objects. Not all wats have mondops, but those that do tend to keep them decoratively simple. Excellent examples of mondops can be found at the Sukhothai ruins in central Thailand, where they house colossal stone Buddhas.

The library or ho trai is where sacred texts are housed. These structures are sometimes built on stilts over a pond, while others have basements or first floors made of brick. In both instances, the purpose is to prevent insects from destroying manuscripts. A sala is an open air pavilion. At a temple complex, it is the place where monks can relax, since their living quarters tend to be quite small. Other buildings you may come across at a wat are the monk’s quarters called kuti, a crematorium (easily identified by it tall chimney rising from the center of the roof), a belfry, and a drum tower.